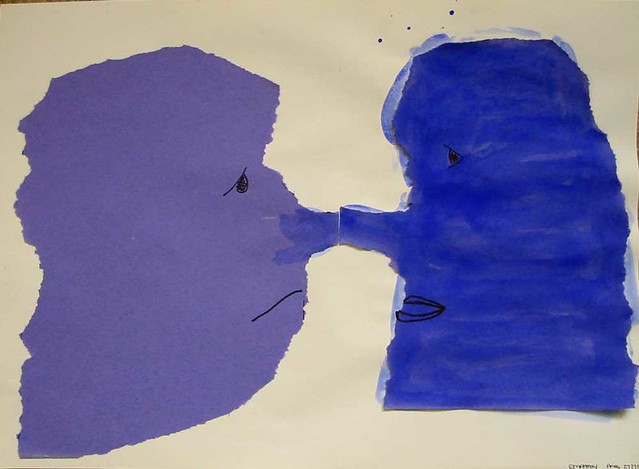

Empathy by The Shopping Sherpa

Another Sunday morning, another stimulating conversation about medical education on Twitter.

It started with a tweet from Dr. Jonathon Tomlinson “To say you cannot learn insight and empathy is like saying you cannot learn science or a new language. Possibly true, but very sad.”

So can we teach empathy? What do we mean by empathy? A good review of the complexities was published earlier this year by some researchers from the University of East Anglia. They suggest that we might be better to step away from the concept of empathy and instead just focus on etiquette. It's a provocative read.

I wonder if teaching empathy isn't like teaching clinical reasoning. We need to first think of empathy as a disposition before concentrating on the skills. The following quote comes from a just-published study on how physicians think about clinical reasoning in students, is it an ability or a disposition? : "The ability-disposition distinction highlights the difference between teaching knowledge and skills, referred to as teaching-as-transmission, versus teaching attitudes, modifying personality and changing behaviour, referred to as teaching-as-enculturation."

So how can we transmit what we think is important to others about empathy? A few years ago, I blogged about a communication skills session that I was teaching. I was aware of how this session on "breaking bad news" had to some become formulaic. But an interesting discussion did occur and we all questioned our thoughts and approaches to the topic.

Just as Krupat et. al suggest that in order to develop clinical reasoning we need to focus on "encouraging self-awareness and mindfulness, modelling open discussion and inquiry, accepting doubt and uncertainty", I'd suggest that the same is true of developing empathy.

What we do not want is for students to leave thinking that empathy is just a set of behaviours. As this doctor tweeted: ""Empathy by rote" is a ridiculous concept. It's like teaching somebody to be "happy". Faked empathy is insulting."

Another doctor replied that to his mind one of the worst examples of this was: “ to score on 'empathy' student said 'sorry it has to be me to tell you this'”. The doctor was shocked as he saw this as the student putting “professional discomfort before patient distress”. It’s this kind of situation that we exactly need to tease out when talking to students about empathy and communication.

In a comment on a blog post by a doctor about breaking bad news, a patient writes of her feeling when she was told she had a serious condition. She explains how the doctor “As he spoke, he began to sip little bits of air in between his lips. This suggested to me he was feeling emotions as well. It made him more human and incredibly compassionate. I loved him for that.”

For some patients showing that we are human and have emotions to will be right. For others it might be seen selfish. They might want us to have ‘professional distance’, to just get on with the job. How with someone that we don’t know well can we figure out how to be? Do we have to accept that sometimes we will just get it wrong and that etiquette is the best we can aim for?

I don’t expect to reach the answers to those questions through this blog. But they are the kind of issues we should discuss with students when we are in real-life situations, so that we can help them to start developing their sensitivity to communication and their inclination to becoming good communicators.

More tweets can be seen in the storify here.

Regina Holliday tells the powerful story of a doctor who seems to lack all empathy here.

Excellent post on empathy by oncologist, Robert Miller, here.

Previous posts on medical students' thoughts about teaching and learning about empathy:

A medical student's thoughts on empathy and #meded

A twitter conversation with UK medical students about empathy

More tweets can be seen in the storify here.

Regina Holliday tells the powerful story of a doctor who seems to lack all empathy here.

Excellent post on empathy by oncologist, Robert Miller, here.

Previous posts on medical students' thoughts about teaching and learning about empathy:

A medical student's thoughts on empathy and #meded

A twitter conversation with UK medical students about empathy